Yivrian has been conceived as a member of a language family, though none of the other members of the family have ever seen significant development. This presented me with a challenge and an opportunity when I sat down to write my current WiP, since it’s set in a part of the world that doesn’t speak Yivrian, but one of its sister languages Praseo.

Praseo, known as Praçí in an earlier incarnation, is the language of the city of Prasa (formerly Praç) and its environs. Praseo was originally conceived as a Portuguese-like relative of Yivrian, and it retains several features from that early stage: nasal vowels, several syllable reductions, and vocalization of coda -l to create lots of diphthongs ending in -o. However, over time that Portuguese flavor has largely been lost, partly because my conception of the conculture of the Yivrian cultural area changed quite a bit, and partly because the Yivrian lexical base was hard to warp into something that felt Romance-like. The current incarnation has phonoaesthetic elements of Japanese and Pacific Northwest Native American languages to go with the Portuguese substrate, but it retains enough similarity to Yivrian to feel like a member of the same family.

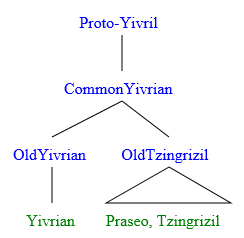

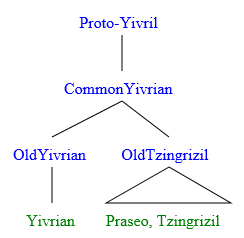

But I may be getting ahead of myself. Let me show you a chart of Yivrian’s close relatives:

There is not a lot of breadth here, as the near relatives of Yivrian number only two (plus a possible, unnamed third language which I haven’t included in the chart above, since it’s little more than conjecture at this point). For brevity, I often refer to the languages mentioned above with the following abbreviations:

- PY (Proto-Yivril)

- CY (Common Yivrian)

- OY (Old Yivrian)

- OTz (Old Tzingrizil)

- Y (Yivrian)

- Pr (Praseo)

- Tz (Tzingrizil)

[Speaking from an in-universe perspective:] Yivrian, Praseo, and Tzingrizil are all attested, literary languages that had hundreds of thousands of speakers during the classical period and are quite well-documented. The “old” languages Old Yivrian and Old Tzingrizil are also attested, though much more sparsely, while the ancestral languages of Common Yivrian and Proto-Yivril are only known through reconstruction. There is a pretty high level of intelligibility between OY and OTz, though the daughter languages are all mutually unintelligible.

[Speaking from a conlanging perspective:] My Yivrian lexicon includes the ancestral Common Yivrian forms for all of its entries (except those that are borrowings or later coinages, obviously), which means that I have a pretty large CY lexical base to use for deriving other sister languages. The challenge that this presents, though, is to create forms that are phonoaesthetically pleasing and linguistically plausible for the other daughter languages. Y itself doesn’t have this problem, since all of the CY forms in the lexicon were created by extrapolating backwards from Y, but I find that the sound changes from CY forward to the other daughters require a lot of tweaking. Next post I may go into detail on a few of the problems I encountered and some solutions that I worked up for them.

But using Praseo for my WiP actually presented a bigger problem. Namely, the people in the book don’t actually speak Praseo yet.

The book I’m working on is set in an early part of the Yivrian history, at the stage of Old Yivrian and Old Tzingrizil. The story takes place in and around Prasa, but at the time of the story Prasa had been settled by explorers from Tsingris for only about two generations. So the characters are largely speaking OTz. But I don’t want to use OTz for my names and language snippets, because OTz is ugly. I have strong phonoaesthetic expectations for my conlangs, especially those that are going to go into books. I consider OY and OTz to be intermediate stages, and I don’t much worry about tuning them, but this means that they aren’t suitable for use as the main conlang sources in a novel. Furthermore, I have to keep my readers in mind — it would be really confusing if I publish three different novels in different time periods, and all of the place names were slightly different in each book due to linguistic shifts.

To get around these problems, I established a policy which I intend to follow from here on out. All place names and language snippets appear in the canonical, classical form of each language, which is generally the latest developed form of the language in con-historical time. Furthermore, wherever possible place names are given in the form of the local language, regardless of the language of the speaker or POV character in the story. That is, the city of Prasa will always be called Prasa, since that’s its name in Praseo, despite the fact that in Y the name is Parath, and in Tz it’s something else yet.

But all of this is just backstory and extra-literary justification for my linguistic decisions. The actual work of creating Praseo is still underway, and next week I’ll talk about some of the challenges.